The Weight of Words: Rethinking ‘Inmate’ in Prison Education

That word Inmate

Criminal justice reform advocates and people who work with incarcerated students have advised that we not use this word when talking about people who are in prison facilities. COs use this word and sometimes they use this word as a means to degrade and enforce their power over the prison population. A reader recently reminded me that this word is not in use anymore. As an English professor and a writer, the use of words is my business, so word usage and effect is always interesting. A writer cannot guess every reaction and cannot please everyone, but looking at words is important because our words have power. This is my deep dive into the use of the word inmate:

Someone suggested problems with using that word when I first began teaching in the prisons, but it snuck back into my writing for a couple of reasons:

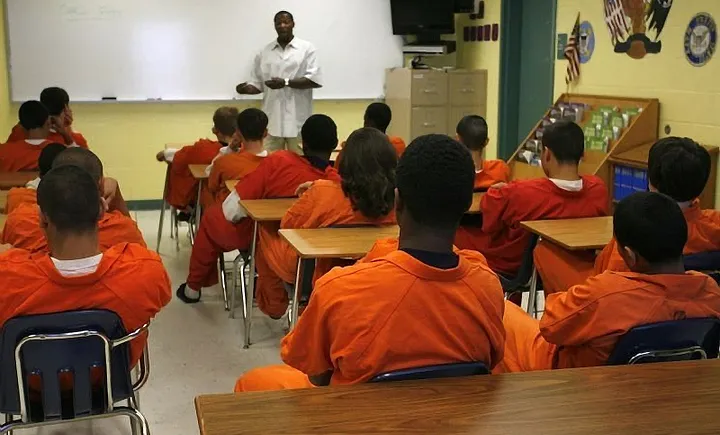

I interact with the COs and administrators in the facilities who use that word. They use it to enforce their power and authority over the people inside. I am not a CO. My purpose in there is to teach them and not to lord my power over them. I have increased power in there automatically because I can call a CO and get them kicked out of my classroom. I can also get them kicked out of the program. This is a huge power differential, and I recognize that when interacting with my students. They need to be comfortable enough to learn, and they will not be if I am constantly calling in the COs or threatening their status in the program. Using the word inmate can conjure up this power dynamic. By working in this environment, with COs as well as with justice impacted individuals, my language changes to reflect the language around me. The COs call them inmates. That word is in use every day. The students hear that word every day. The COs call the students by their last names. They have sometimes insisted as a policy that professors do the same. I have taken that as a “suggestion” more than a policy for a few reasons. Again, not a CO. Educating the students requires more of a relationship with them than appropriate or safe for a CO. It might be perceived by other COs or other students as overly familiar, which may or may not be safe for them. As an English professor, I cannot really speak to their policies and procedures about what is or is not safe for them in their work.

The second reason is that I discuss my work with others who do not work inside the prisons, and inmate is an easy short hand. There are other labels to use of course: incarcerated students, justice impacted students, prison population, and student population in the facilities. It becomes necessary to actually label the students as incarcerated students especially when meeting with people and administrators from other departments. The students have limited resources and people who are working with them have a different perspective about what they need or want in their classes. We cannot pretend that they do not have more obstacles than other students. The incarcerated students never forget where they are, and we should not either, or else we do them a disservice.

In addition to the two other reasons this word has slipped back in my language, the name of the program I work in is called the Inmate Scholar’s Program. There was a conversation about the use of this word as a title for our program at a recent meeting. The consensus was that we should change the name and that the higher ups were going to discuss it further to decide what the name should be. We need a name that labels what we are doing and who we are working with without using a derogatory name for that group. The chat immediately filled up with suggestions, and one of our team members wrote them down. Something will eventually come of this list, but it is unclear how much input we will have about the change. In this blog, I will replace the name of our program in all references until we get a new name.

So, this brings us back to the main question: Should we use the term inmate when talking about our student population? I sometimes resist change as a knee-jerk reaction, but that is not productive and not representative of the type of person that I want to be. In discussions with other writers and professors, there appear to be two main camps of thought on this. Some think we have gone too far in policing language. Some think we have not gone far enough. Some formerly and currently incarcerated people use this word to describe themselves and approve other people using this word as well. My conclusion is that the use of this word is on its way out. I have decided to edit it out in my previous blog posts. (Please let me know if I have forgotten one!) Angelica Perez, one of the managers of my program, said she mostly views blogs “as going on a journey” with the writer. I love that description, and this is my journey, and the way I see the work I am doing. Since this entry is my examination of the use of this word, I have invited the reader on this journey. When looking back at some of my opinions and word choices, I am sure to feel some remorse or shame. All growth is uncomfortable. Even if I do, that does not negate my current experience.

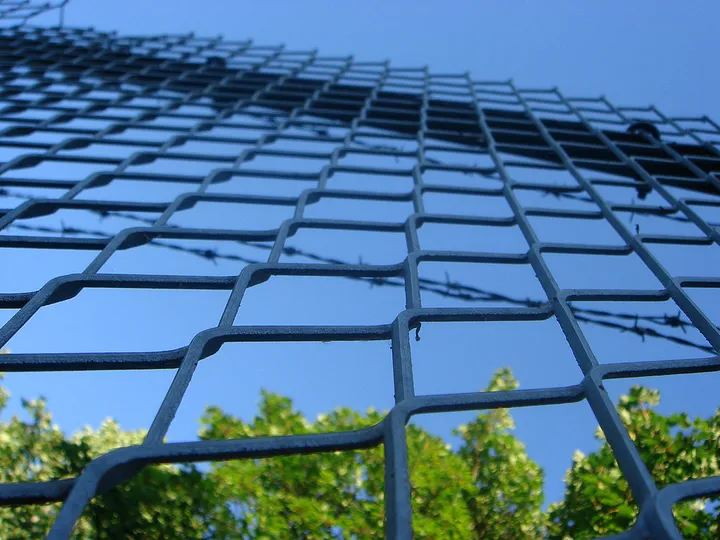

Teaching in these facilities is a balancing act between trying to educate people who are in horrible circumstances, and avoiding being consumed by the students’ stories or this setting. Maybe I use the word so that I can manufacture a boundary between us? Maybe that is one of the reason the COs use it? And maybe that is why we use this word at all? Somehow, the word inmate defines a boundary between us and them. We (nonimates) would not ever find ourselves in that position and somehow they are less than or not deserving of their freedom because they are classified as inmates, which is not true and not fair. I am going to try to never use this word, and I am going to find a way to establish the needed boundaries to continue this work without putting them in this separate, unequal category. They are people. Education should be a right for everyone.

That word Inmate

Criminal justice reform advocates and people who work with incarcerated students have advised that we not use this word when talking about people who are in prison facilities. COs use this word and sometimes they use this word as a means to degrade and enforce their power over the prison population. A reader recently reminded me that this word is not in use anymore. As an English professor and a writer, the use of words is my business, so word usage and effect is always interesting. A writer cannot guess every reaction and cannot please everyone, but looking at words is important because our words have power. This is my deep dive into the use of the word inmate:

Someone suggested problems with using that word when I first began teaching in the prisons, but it snuck back into my writing for a couple of reasons:

I interact with the COs and administrators in the facilities who use that word. They use it to enforce their power and authority over the people inside. I am not a CO. My purpose in there is to teach them and not to lord my power over them. I have increased power in there automatically because I can call a CO and get them kicked out of my classroom. I can also get them kicked out of the program. This is a huge power differential, and I recognize that when interacting with my students. They need to be comfortable enough to learn, and they will not be if I am constantly calling in the COs or threatening their status in the program. Using the word inmate can conjure up this power dynamic. By working in this environment, with COs as well as with justice impacted individuals, my language changes to reflect the language around me. The COs call them inmates. That word is in use every day. The students hear that word every day. The COs call the students by their last names. They have sometimes insisted as a policy that professors do the same. I have taken that as a “suggestion” more than a policy for a few reasons. Again, not a CO. Educating the students requires more of a relationship with them than appropriate or safe for a CO. It might be perceived by other COs or other students as overly familiar, which may or may not be safe for them. As an English professor, I cannot really speak to their policies and procedures about what is or is not safe for them in their work.

The second reason is that I discuss my work with others who do not work inside the prisons, and inmate is an easy short hand. There are other labels to use of course: incarcerated students, justice impacted students, prison population, and student population in the facilities. It becomes necessary to actually label the students as incarcerated students especially when meeting with people and administrators from other departments. The students have limited resources and people who are working with them have a different perspective about what they need or want in their classes. We cannot pretend that they do not have more obstacles than other students. The incarcerated students never forget where they are, and we should not either, or else we do them a disservice.

In addition to the two other reasons this word has slipped back in my language, the name of the program I work in is called the Inmate Scholar’s Program. There was a conversation about the use of this word as a title for our program at a recent meeting. The consensus was that we should change the name and that the higher ups were going to discuss it further to decide what the name should be. We need a name that labels what we are doing and who we are working with without using a derogatory name for that group. The chat immediately filled up with suggestions, and one of our team members wrote them down. Something will eventually come of this list, but it is unclear how much input we will have about the change. In this blog, I will replace the name of our program in all references until we get a new name.

So, this brings us back to the main question: Should we use the term inmate when talking about our student population? I sometimes resist change as a knee-jerk reaction, but that is not productive and not representative of the type of person that I want to be. In discussions with other writers and professors, there appear to be two main camps of thought on this. Some think we have gone too far in policing language. Some think we have not gone far enough. Some formerly and currently incarcerated people use this word to describe themselves and approve other people using this word as well. My conclusion is that the use of this word is on its way out. I have decided to edit it out in my previous blog posts. (Please let me know if I have forgotten one!) Angelica Perez, one of the managers of my program, said she mostly views blogs “as going on a journey” with the writer. I love that description, and this is my journey, and the way I see the work I am doing. Since this entry is my examination of the use of this word, I have invited the reader on this journey. When looking back at some of my opinions and word choices, I am sure to feel some remorse or shame. All growth is uncomfortable. Even if I do, that does not negate my current experience.

Teaching in these facilities is a balancing act between trying to educate people who are in horrible circumstances, and avoiding being consumed by the students’ stories or this setting. Maybe I use the word so that I can manufacture a boundary between us? Maybe that is one of the reason the COs use it? And maybe that is why we use this word at all? Somehow, the word inmate defines a boundary between us and them. We (nonimates) would not ever find ourselves in that position and somehow they are less than or not deserving of their freedom because they are classified as inmates, which is not true and not fair. I am going to try to never use this word, and I am going to find a way to establish the needed boundaries to continue this work without putting them in this separate, unequal category. They are people. Education should be a right for everyone.

That word Inmate

Criminal justice reform advocates and people who work with incarcerated students have advised that we not use this word when talking about people who are in prison facilities. COs use this word and sometimes they use this word as a means to degrade and enforce their power over the prison population. A reader recently reminded me that this word is not in use anymore. As an English professor and a writer, the use of words is my business, so word usage and effect is always interesting. A writer cannot guess every reaction and cannot please everyone, but looking at words is important because our words have power. This is my deep dive into the use of the word inmate:

Someone suggested problems with using that word when I first began teaching in the prisons, but it snuck back into my writing for a couple of reasons:

I interact with the COs and administrators in the facilities who use that word. They use it to enforce their power and authority over the people inside. I am not a CO. My purpose in there is to teach them and not to lord my power over them. I have increased power in there automatically because I can call a CO and get them kicked out of my classroom. I can also get them kicked out of the program. This is a huge power differential, and I recognize that when interacting with my students. They need to be comfortable enough to learn, and they will not be if I am constantly calling in the COs or threatening their status in the program. Using the word inmate can conjure up this power dynamic. By working in this environment, with COs as well as with justice impacted individuals, my language changes to reflect the language around me. The COs call them inmates. That word is in use every day. The students hear that word every day. The COs call the students by their last names. They have sometimes insisted as a policy that professors do the same. I have taken that as a “suggestion” more than a policy for a few reasons. Again, not a CO. Educating the students requires more of a relationship with them than appropriate or safe for a CO. It might be perceived by other COs or other students as overly familiar, which may or may not be safe for them. As an English professor, I cannot really speak to their policies and procedures about what is or is not safe for them in their work.

The second reason is that I discuss my work with others who do not work inside the prisons, and inmate is an easy short hand. There are other labels to use of course: incarcerated students, justice impacted students, prison population, and student population in the facilities. It becomes necessary to actually label the students as incarcerated students especially when meeting with people and administrators from other departments. The students have limited resources and people who are working with them have a different perspective about what they need or want in their classes. We cannot pretend that they do not have more obstacles than other students. The incarcerated students never forget where they are, and we should not either, or else we do them a disservice.

In addition to the two other reasons this word has slipped back in my language, the name of the program I work in is called the Inmate Scholar’s Program. There was a conversation about the use of this word as a title for our program at a recent meeting. The consensus was that we should change the name and that the higher ups were going to discuss it further to decide what the name should be. We need a name that labels what we are doing and who we are working with without using a derogatory name for that group. The chat immediately filled up with suggestions, and one of our team members wrote them down. Something will eventually come of this list, but it is unclear how much input we will have about the change. In this blog, I will replace the name of our program in all references until we get a new name.

So, this brings us back to the main question: Should we use the term inmate when talking about our student population? I sometimes resist change as a knee-jerk reaction, but that is not productive and not representative of the type of person that I want to be. In discussions with other writers and professors, there appear to be two main camps of thought on this. Some think we have gone too far in policing language. Some think we have not gone far enough. Some formerly and currently incarcerated people use this word to describe themselves and approve other people using this word as well. My conclusion is that the use of this word is on its way out. I have decided to edit it out in my previous blog posts. (Please let me know if I have forgotten one!) Angelica Perez, one of the managers of my program, said she mostly views blogs “as going on a journey” with the writer. I love that description, and this is my journey, and the way I see the work I am doing. Since this entry is my examination of the use of this word, I have invited the reader on this journey. When looking back at some of my opinions and word choices, I am sure to feel some remorse or shame. All growth is uncomfortable. Even if I do, that does not negate my current experience.

Teaching in these facilities is a balancing act between trying to educate people who are in horrible circumstances, and avoiding being consumed by the students’ stories or this setting. Maybe I use the word so that I can manufacture a boundary between us? Maybe that is one of the reason the COs use it? And maybe that is why we use this word at all? Somehow, the word inmate defines a boundary between us and them. We (nonimates) would not ever find ourselves in that position and somehow they are less than or not deserving of their freedom because they are classified as inmates, which is not true and not fair. I am going to try to never use this word, and I am going to find a way to establish the needed boundaries to continue this work without putting them in this separate, unequal category. They are people. Education should be a right for everyone.