The Inherent Worth and Dignity of Every Person: A UU’s Journey into Prison Education

**This is a speech I gave at my local Unitarian Universalist Church. It was recorded, so I will upload that video as soon as it is available, but here is a copy of it for now.**

Morning everyone,

Morning everyone,

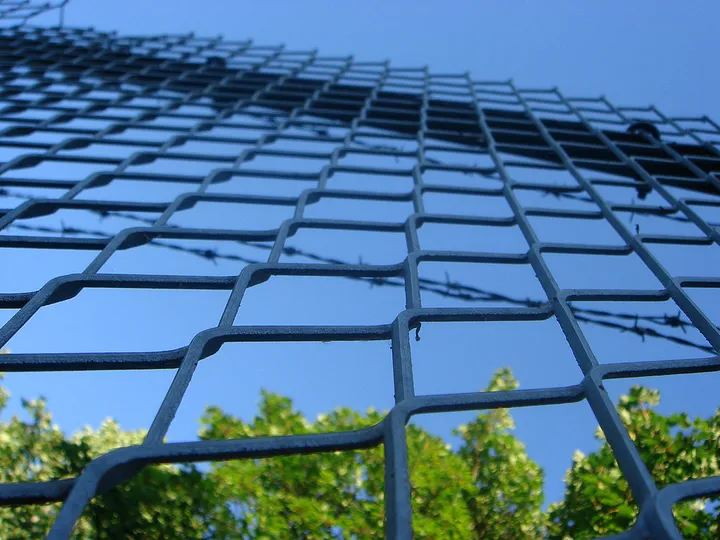

Most of you know me. My name is Sara Wallace, and I am an English instructor at Bakersfield College and with the Rising Scholars Program or the RSP, which is the name of the prison education program at Bakersfield College. Since 2019, many of my classes have been located inside one of the prison facilities that we have in our county. I have taught at Wasco, Corcoran, SATF, Kern Valley, North Kern, and McFarland (when it was a prison and not an immigration detention center). I have also taught at some of the juvenile hall centers. I have taught composition and reading, literature, Shakespeare, Latino Literature, and creative writing. I have taught in-person, via correspondence and through cell doors. It has been a very rewarding and stressful experience so far, but I believe (as many of us who work inside do) that this is work that is worth doing.

Our first principle as UUs is “The inherent worth and dignity of every person” and our second principle is “justice, equity and compassion in human relations.” My work in the prison is closely tied to my committment to these first two principles. I was a Unitarian Universalist before I knew anything about it because I believed in our seven principles always.

My colleagues on BC’s campus are generally supportive and believe in this work, but most of them do not want to actually do it. I do not really blame them. It is hard work and filled with obstacles. I have to get a TB test sometimes every six months, fill out paper work for each individual prison, go to meetings, and professional development seminars. I have to get all my material and my technology pre-approved by the warden every semester. My commute is anywhere from 45 minutes to an hour and 15 minutes one way. All of my students have to write their essays by hand, which is challenging for them to do and for me to read. Sometimes there are lock downs, and I am not allowed to go inside. This can be due to a variety of reasons: security, COVID, or even a scheduled search. Often I do not know the reason why, but I adjust my lesson plans and go home hoping I can get in there the following week. Correspondence classes were absolutely the worst. I was trying to teach English through the mail essentially, except we were not using the mostly reliable U.S. postal system. Instead, I was driving the work to BC, putting it in a tub, and then someone was driving it to the prison to be handed out by someone else. I was not getting their work at all as it was getting lost frequently. They had a lot of questions that I would attempt to answer, but I had no idea if they were getting my letters. Luckily, we are transitioning out of correspondence classes. I have been pretty vocal about my hatred for it, so hopefully I will not be stuck in that position again.

Now that you know about the many obstacles we have when teaching on the inside, I want you to know about our students and why we want to do it. All of my students are pretty motivated. They do the work. They do the homework. They do the reading. They participate in discussion without strong arming. They are pretty well read. They ask me complicated questions that I then have to look up when I get home. Some people have said to me: “Well, of course they do the work. They do not have anything else to do!” That is definitely not true. All of my students have other jobs. Many of them are getting certified as drug and alcohol counselors. A lot of them are taking 4 or 5 or even 6 classes (I tell them not to…it is too much!). They have scheduled phone calls and visits with family. They are not allowed to just hang out in their cells and do their homework. Their time is limited and sometimes they have to go outside or go to work, so they do have other things in their day that they need to get done besides the work for my class, but they still do it. It is important to them. They like that I hold them to a high standard. They are extremely competitive and often learn information about subjects just because they want to know, which is a quality that we both share. They are challenging and so is the work.

The two questions that I am most frequently asked are: “are you scared?” and “are you safe?” I have never felt unsafe in the prison. I have frequently felt unsafe teaching on the outside. You are usually on your own on the outside, and I have had some scary situations and taught in places by myself at night with no one else around. That has scared me. Teaching inside has not scared me. I have no idea what these students have done. I do not know if they are still affiliated with gangs, or how long their sentences are. I do this on purpose. My job inside is not to punish them or to judge them for their past actions, but to teach them how to write an academic essay or analyze literature. I can do that. I do not know how to deal with the other things.

Sometimes a student will tell me what happened, but that is not the norm. Occasionally, students will start talking about yard politics or violence inside the prison (which I am very curious about but do not ask about), and another student will ask them to stop and say they are going to freak me out. They want me to feel comfortable in there so that I will stay. They want to take classes. If I had been the victim of their crime, I would probably feel differently about them. I am sure it would be harder to disconnect the person from the crime, and I acknowledge that. I do not know their story or their situation, but that is not for me to know. I try to stay in my lane. I also cannot be a social justice warrior in there. I can advocate for them outside by getting them more resources or more classes, but inside, I am there to teach them. Besides that, there is a culture in the prison that professors and teachers are not to be messed with. If someone did mess with me, they would have problems with other people on the yard. This is a program that the incarcerated students want, and they will take issue with the person who jeopardizes that. Besides prison culture as a safety net, I also have ways to get help if something went down in the classroom. I have an alarm and a whistle, and usually there is a correction’s officer (or a CO) nearby to keep an eye on things (not always, but usually).

I recently attended a full-day workshop with other people who work inside. During one of our break out sessions, we were discussing faculty recruitment. I said I was not sure what the fear was about working inside. I did not understand it. I felt like it was mostly fear of the unknown. One of my colleagues said, “but it is traumatic to work inside, right?” I said, “yes, sometimes,” but then I went home and thought about it. I really do not feel traumatized. I asked my husband if that was unusual. Should I feel traumatized? He said what he always says when I ask him these kinds of questions: “No. You are fine.” I think what I experience mostly is vicarious trauma. I feel deep empathy for their situation and sometimes I have to distance myself from that feeling in order to do my work. They are in cells for a lot of the day. They cannot see their children. One of my students’ daughters this semester is getting married. Another student told the woman he was in love with to find someone else when he was sentenced. Even the glimpses into their lives behind bars is heart breaking. My first semester a student asked me what I thought of all this, and I said: “I cannot imagine what you guys are going through.”

It is hugely fulfilling though. It makes me feel really uncomfortable when people talk about how brave I am and how wonderful it is that I would do this. I like it. I am having fun. I get to teach motivated students, and I get to teach a lot of subjects that I would not get to teach on campus, so it feels weird for people to applaud me for a sacrifice I do not feel I am making. I do like to tell people that I teach inside because it is good for the ego, and I do have one, but other than that, I am really enjoying what I am doing.

Conservatives have been known to rail against the idea of prison education and some have also expressed anger at this program. Why should criminals get free education when we have to pay for ours? I have never heard this statement directly, but many of my colleagues have. If it is said to me, my response will be: “well, education should be free for everyone, so…” Many believe that people who have done something wrong should be punished and that offering education is not what prison should be about. First of all, many of them will be released back into society. What do we expect them to do if they do not have any skills or education? This is helpful for society in general. Many of them did not have the opportunity to have a good education before they were sent to prison. Many of them were also given longer sentences or did not have a good defence attorney because of poverty or racism. There are a lot of things at play here. Education can help society as a whole and these people individually. It even helps lessen the violence in the prison while they are in there. If they are reading Shakespeare and writing papers for me, then they will definitely not have time for other things. They also need to remain without incident or else they cannot come back into the classroom, which is where they want to be. This helps everyone. CDCR is concerned with safety as it should be, and coming into the prison is a risk, but it is balanced by the improved attitudes, decrease in violence, and the increase in employment opportunities after they are released.

This semester I am teaching Shakespeare and Overview of Literature to a group of guys that I taught Composition and Reading to last semester. This is pretty unusual. The RSP likes to shift everyone around so that you do not teach the same students because you can get attached, but there are only so many professors and so I expect I will end up teaching students for multiple semesters. The reason this happened this time around is that last semester a student in another class walked by my classroom, asked me what I was teaching and then asked me what I could teach. I gave him a list, and he asked me if I could get Shakespeare in here. I said: get together an inquiry form with a list of students who want Shakespeare, and they will give it to you. They did, and many of my previous students signed up, and now I am teaching them Shakespeare. One of my students asked me about Sir Walter Raleigh when I was giving an historical context lesson. I did not know much about him other than he was a poet, so I returned the following week with a full-page of information about him. The student just knew that he was from the same era. I end up with lists of questions from them that I then have to research. Another student asked me last week if the people in the Othello movie we were watching are speaking the same language as the people in the Romeo and Juliet movie we saw a couple of weeks ago. I said: yes, it is all Shakespearean English. The ones we are watching now are just doing it with English accents. He said, how come I can understand this one and not the other one? I said: you are just getting it now. It is just easier. I did a little dance in the parking lot about it. It was a huge win! One of my students wanted more opportunities to publish his academic work, and now I am forming a committee to figure out how to get them more information about that. In a previous semester, a student showed me his proposal for a book club based on the informal discussions we got into in our Latino Literature class.

These students are hard working and thirsty for knowledge. I feel lucky to be able to teach them. I was recently at a conference about introducing board games into the learning environment put on by my colleague Dr. Christine Cruz Boone. Besides it being a wonderful idea, (The RSP are going to start trying to figure out how to do that in our work inside), one of the many issues that were discussed during this presentation is the lack of interest and general apathy of our on-campus students. The tap dancing we have to go through to get some of our students to participate at all is one of the many frustrations of our work as educators. Out of all the many frustrations about working in prison, this is not one of them. There is not much I would not do to teach students who are this engaged — no matter what they have done. They are working on themselves now, and they want to learn. It is important that we give them this opportunity to better their lives. Some want to put them away and forget about them, but they have inherent worth and dignity no matter what they have done, and we should treat them with justice, equity and compassion as human beings.

**This is a speech I gave at my local Unitarian Universalist Church. It was recorded, so I will upload that video as soon as it is available, but here is a copy of it for now.**

Morning everyone,

Morning everyone,

Most of you know me. My name is Sara Wallace, and I am an English instructor at Bakersfield College and with the Rising Scholars Program or the RSP, which is the name of the prison education program at Bakersfield College. Since 2019, many of my classes have been located inside one of the prison facilities that we have in our county. I have taught at Wasco, Corcoran, SATF, Kern Valley, North Kern, and McFarland (when it was a prison and not an immigration detention center). I have also taught at some of the juvenile hall centers. I have taught composition and reading, literature, Shakespeare, Latino Literature, and creative writing. I have taught in-person, via correspondence and through cell doors. It has been a very rewarding and stressful experience so far, but I believe (as many of us who work inside do) that this is work that is worth doing.

Our first principle as UUs is “The inherent worth and dignity of every person” and our second principle is “justice, equity and compassion in human relations.” My work in the prison is closely tied to my committment to these first two principles. I was a Unitarian Universalist before I knew anything about it because I believed in our seven principles always.

My colleagues on BC’s campus are generally supportive and believe in this work, but most of them do not want to actually do it. I do not really blame them. It is hard work and filled with obstacles. I have to get a TB test sometimes every six months, fill out paper work for each individual prison, go to meetings, and professional development seminars. I have to get all my material and my technology pre-approved by the warden every semester. My commute is anywhere from 45 minutes to an hour and 15 minutes one way. All of my students have to write their essays by hand, which is challenging for them to do and for me to read. Sometimes there are lock downs, and I am not allowed to go inside. This can be due to a variety of reasons: security, COVID, or even a scheduled search. Often I do not know the reason why, but I adjust my lesson plans and go home hoping I can get in there the following week. Correspondence classes were absolutely the worst. I was trying to teach English through the mail essentially, except we were not using the mostly reliable U.S. postal system. Instead, I was driving the work to BC, putting it in a tub, and then someone was driving it to the prison to be handed out by someone else. I was not getting their work at all as it was getting lost frequently. They had a lot of questions that I would attempt to answer, but I had no idea if they were getting my letters. Luckily, we are transitioning out of correspondence classes. I have been pretty vocal about my hatred for it, so hopefully I will not be stuck in that position again.

Now that you know about the many obstacles we have when teaching on the inside, I want you to know about our students and why we want to do it. All of my students are pretty motivated. They do the work. They do the homework. They do the reading. They participate in discussion without strong arming. They are pretty well read. They ask me complicated questions that I then have to look up when I get home. Some people have said to me: “Well, of course they do the work. They do not have anything else to do!” That is definitely not true. All of my students have other jobs. Many of them are getting certified as drug and alcohol counselors. A lot of them are taking 4 or 5 or even 6 classes (I tell them not to…it is too much!). They have scheduled phone calls and visits with family. They are not allowed to just hang out in their cells and do their homework. Their time is limited and sometimes they have to go outside or go to work, so they do have other things in their day that they need to get done besides the work for my class, but they still do it. It is important to them. They like that I hold them to a high standard. They are extremely competitive and often learn information about subjects just because they want to know, which is a quality that we both share. They are challenging and so is the work.

The two questions that I am most frequently asked are: “are you scared?” and “are you safe?” I have never felt unsafe in the prison. I have frequently felt unsafe teaching on the outside. You are usually on your own on the outside, and I have had some scary situations and taught in places by myself at night with no one else around. That has scared me. Teaching inside has not scared me. I have no idea what these students have done. I do not know if they are still affiliated with gangs, or how long their sentences are. I do this on purpose. My job inside is not to punish them or to judge them for their past actions, but to teach them how to write an academic essay or analyze literature. I can do that. I do not know how to deal with the other things.

Sometimes a student will tell me what happened, but that is not the norm. Occasionally, students will start talking about yard politics or violence inside the prison (which I am very curious about but do not ask about), and another student will ask them to stop and say they are going to freak me out. They want me to feel comfortable in there so that I will stay. They want to take classes. If I had been the victim of their crime, I would probably feel differently about them. I am sure it would be harder to disconnect the person from the crime, and I acknowledge that. I do not know their story or their situation, but that is not for me to know. I try to stay in my lane. I also cannot be a social justice warrior in there. I can advocate for them outside by getting them more resources or more classes, but inside, I am there to teach them. Besides that, there is a culture in the prison that professors and teachers are not to be messed with. If someone did mess with me, they would have problems with other people on the yard. This is a program that the incarcerated students want, and they will take issue with the person who jeopardizes that. Besides prison culture as a safety net, I also have ways to get help if something went down in the classroom. I have an alarm and a whistle, and usually there is a correction’s officer (or a CO) nearby to keep an eye on things (not always, but usually).

I recently attended a full-day workshop with other people who work inside. During one of our break out sessions, we were discussing faculty recruitment. I said I was not sure what the fear was about working inside. I did not understand it. I felt like it was mostly fear of the unknown. One of my colleagues said, “but it is traumatic to work inside, right?” I said, “yes, sometimes,” but then I went home and thought about it. I really do not feel traumatized. I asked my husband if that was unusual. Should I feel traumatized? He said what he always says when I ask him these kinds of questions: “No. You are fine.” I think what I experience mostly is vicarious trauma. I feel deep empathy for their situation and sometimes I have to distance myself from that feeling in order to do my work. They are in cells for a lot of the day. They cannot see their children. One of my students’ daughters this semester is getting married. Another student told the woman he was in love with to find someone else when he was sentenced. Even the glimpses into their lives behind bars is heart breaking. My first semester a student asked me what I thought of all this, and I said: “I cannot imagine what you guys are going through.”

It is hugely fulfilling though. It makes me feel really uncomfortable when people talk about how brave I am and how wonderful it is that I would do this. I like it. I am having fun. I get to teach motivated students, and I get to teach a lot of subjects that I would not get to teach on campus, so it feels weird for people to applaud me for a sacrifice I do not feel I am making. I do like to tell people that I teach inside because it is good for the ego, and I do have one, but other than that, I am really enjoying what I am doing.

Conservatives have been known to rail against the idea of prison education and some have also expressed anger at this program. Why should criminals get free education when we have to pay for ours? I have never heard this statement directly, but many of my colleagues have. If it is said to me, my response will be: “well, education should be free for everyone, so…” Many believe that people who have done something wrong should be punished and that offering education is not what prison should be about. First of all, many of them will be released back into society. What do we expect them to do if they do not have any skills or education? This is helpful for society in general. Many of them did not have the opportunity to have a good education before they were sent to prison. Many of them were also given longer sentences or did not have a good defence attorney because of poverty or racism. There are a lot of things at play here. Education can help society as a whole and these people individually. It even helps lessen the violence in the prison while they are in there. If they are reading Shakespeare and writing papers for me, then they will definitely not have time for other things. They also need to remain without incident or else they cannot come back into the classroom, which is where they want to be. This helps everyone. CDCR is concerned with safety as it should be, and coming into the prison is a risk, but it is balanced by the improved attitudes, decrease in violence, and the increase in employment opportunities after they are released.

This semester I am teaching Shakespeare and Overview of Literature to a group of guys that I taught Composition and Reading to last semester. This is pretty unusual. The RSP likes to shift everyone around so that you do not teach the same students because you can get attached, but there are only so many professors and so I expect I will end up teaching students for multiple semesters. The reason this happened this time around is that last semester a student in another class walked by my classroom, asked me what I was teaching and then asked me what I could teach. I gave him a list, and he asked me if I could get Shakespeare in here. I said: get together an inquiry form with a list of students who want Shakespeare, and they will give it to you. They did, and many of my previous students signed up, and now I am teaching them Shakespeare. One of my students asked me about Sir Walter Raleigh when I was giving an historical context lesson. I did not know much about him other than he was a poet, so I returned the following week with a full-page of information about him. The student just knew that he was from the same era. I end up with lists of questions from them that I then have to research. Another student asked me last week if the people in the Othello movie we were watching are speaking the same language as the people in the Romeo and Juliet movie we saw a couple of weeks ago. I said: yes, it is all Shakespearean English. The ones we are watching now are just doing it with English accents. He said, how come I can understand this one and not the other one? I said: you are just getting it now. It is just easier. I did a little dance in the parking lot about it. It was a huge win! One of my students wanted more opportunities to publish his academic work, and now I am forming a committee to figure out how to get them more information about that. In a previous semester, a student showed me his proposal for a book club based on the informal discussions we got into in our Latino Literature class.

These students are hard working and thirsty for knowledge. I feel lucky to be able to teach them. I was recently at a conference about introducing board games into the learning environment put on by my colleague Dr. Christine Cruz Boone. Besides it being a wonderful idea, (The RSP are going to start trying to figure out how to do that in our work inside), one of the many issues that were discussed during this presentation is the lack of interest and general apathy of our on-campus students. The tap dancing we have to go through to get some of our students to participate at all is one of the many frustrations of our work as educators. Out of all the many frustrations about working in prison, this is not one of them. There is not much I would not do to teach students who are this engaged — no matter what they have done. They are working on themselves now, and they want to learn. It is important that we give them this opportunity to better their lives. Some want to put them away and forget about them, but they have inherent worth and dignity no matter what they have done, and we should treat them with justice, equity and compassion as human beings.

**This is a speech I gave at my local Unitarian Universalist Church. It was recorded, so I will upload that video as soon as it is available, but here is a copy of it for now.**

Morning everyone,

Morning everyone,

Most of you know me. My name is Sara Wallace, and I am an English instructor at Bakersfield College and with the Rising Scholars Program or the RSP, which is the name of the prison education program at Bakersfield College. Since 2019, many of my classes have been located inside one of the prison facilities that we have in our county. I have taught at Wasco, Corcoran, SATF, Kern Valley, North Kern, and McFarland (when it was a prison and not an immigration detention center). I have also taught at some of the juvenile hall centers. I have taught composition and reading, literature, Shakespeare, Latino Literature, and creative writing. I have taught in-person, via correspondence and through cell doors. It has been a very rewarding and stressful experience so far, but I believe (as many of us who work inside do) that this is work that is worth doing.

Our first principle as UUs is “The inherent worth and dignity of every person” and our second principle is “justice, equity and compassion in human relations.” My work in the prison is closely tied to my committment to these first two principles. I was a Unitarian Universalist before I knew anything about it because I believed in our seven principles always.

My colleagues on BC’s campus are generally supportive and believe in this work, but most of them do not want to actually do it. I do not really blame them. It is hard work and filled with obstacles. I have to get a TB test sometimes every six months, fill out paper work for each individual prison, go to meetings, and professional development seminars. I have to get all my material and my technology pre-approved by the warden every semester. My commute is anywhere from 45 minutes to an hour and 15 minutes one way. All of my students have to write their essays by hand, which is challenging for them to do and for me to read. Sometimes there are lock downs, and I am not allowed to go inside. This can be due to a variety of reasons: security, COVID, or even a scheduled search. Often I do not know the reason why, but I adjust my lesson plans and go home hoping I can get in there the following week. Correspondence classes were absolutely the worst. I was trying to teach English through the mail essentially, except we were not using the mostly reliable U.S. postal system. Instead, I was driving the work to BC, putting it in a tub, and then someone was driving it to the prison to be handed out by someone else. I was not getting their work at all as it was getting lost frequently. They had a lot of questions that I would attempt to answer, but I had no idea if they were getting my letters. Luckily, we are transitioning out of correspondence classes. I have been pretty vocal about my hatred for it, so hopefully I will not be stuck in that position again.

Now that you know about the many obstacles we have when teaching on the inside, I want you to know about our students and why we want to do it. All of my students are pretty motivated. They do the work. They do the homework. They do the reading. They participate in discussion without strong arming. They are pretty well read. They ask me complicated questions that I then have to look up when I get home. Some people have said to me: “Well, of course they do the work. They do not have anything else to do!” That is definitely not true. All of my students have other jobs. Many of them are getting certified as drug and alcohol counselors. A lot of them are taking 4 or 5 or even 6 classes (I tell them not to…it is too much!). They have scheduled phone calls and visits with family. They are not allowed to just hang out in their cells and do their homework. Their time is limited and sometimes they have to go outside or go to work, so they do have other things in their day that they need to get done besides the work for my class, but they still do it. It is important to them. They like that I hold them to a high standard. They are extremely competitive and often learn information about subjects just because they want to know, which is a quality that we both share. They are challenging and so is the work.

The two questions that I am most frequently asked are: “are you scared?” and “are you safe?” I have never felt unsafe in the prison. I have frequently felt unsafe teaching on the outside. You are usually on your own on the outside, and I have had some scary situations and taught in places by myself at night with no one else around. That has scared me. Teaching inside has not scared me. I have no idea what these students have done. I do not know if they are still affiliated with gangs, or how long their sentences are. I do this on purpose. My job inside is not to punish them or to judge them for their past actions, but to teach them how to write an academic essay or analyze literature. I can do that. I do not know how to deal with the other things.

Sometimes a student will tell me what happened, but that is not the norm. Occasionally, students will start talking about yard politics or violence inside the prison (which I am very curious about but do not ask about), and another student will ask them to stop and say they are going to freak me out. They want me to feel comfortable in there so that I will stay. They want to take classes. If I had been the victim of their crime, I would probably feel differently about them. I am sure it would be harder to disconnect the person from the crime, and I acknowledge that. I do not know their story or their situation, but that is not for me to know. I try to stay in my lane. I also cannot be a social justice warrior in there. I can advocate for them outside by getting them more resources or more classes, but inside, I am there to teach them. Besides that, there is a culture in the prison that professors and teachers are not to be messed with. If someone did mess with me, they would have problems with other people on the yard. This is a program that the incarcerated students want, and they will take issue with the person who jeopardizes that. Besides prison culture as a safety net, I also have ways to get help if something went down in the classroom. I have an alarm and a whistle, and usually there is a correction’s officer (or a CO) nearby to keep an eye on things (not always, but usually).

I recently attended a full-day workshop with other people who work inside. During one of our break out sessions, we were discussing faculty recruitment. I said I was not sure what the fear was about working inside. I did not understand it. I felt like it was mostly fear of the unknown. One of my colleagues said, “but it is traumatic to work inside, right?” I said, “yes, sometimes,” but then I went home and thought about it. I really do not feel traumatized. I asked my husband if that was unusual. Should I feel traumatized? He said what he always says when I ask him these kinds of questions: “No. You are fine.” I think what I experience mostly is vicarious trauma. I feel deep empathy for their situation and sometimes I have to distance myself from that feeling in order to do my work. They are in cells for a lot of the day. They cannot see their children. One of my students’ daughters this semester is getting married. Another student told the woman he was in love with to find someone else when he was sentenced. Even the glimpses into their lives behind bars is heart breaking. My first semester a student asked me what I thought of all this, and I said: “I cannot imagine what you guys are going through.”

It is hugely fulfilling though. It makes me feel really uncomfortable when people talk about how brave I am and how wonderful it is that I would do this. I like it. I am having fun. I get to teach motivated students, and I get to teach a lot of subjects that I would not get to teach on campus, so it feels weird for people to applaud me for a sacrifice I do not feel I am making. I do like to tell people that I teach inside because it is good for the ego, and I do have one, but other than that, I am really enjoying what I am doing.

Conservatives have been known to rail against the idea of prison education and some have also expressed anger at this program. Why should criminals get free education when we have to pay for ours? I have never heard this statement directly, but many of my colleagues have. If it is said to me, my response will be: “well, education should be free for everyone, so…” Many believe that people who have done something wrong should be punished and that offering education is not what prison should be about. First of all, many of them will be released back into society. What do we expect them to do if they do not have any skills or education? This is helpful for society in general. Many of them did not have the opportunity to have a good education before they were sent to prison. Many of them were also given longer sentences or did not have a good defence attorney because of poverty or racism. There are a lot of things at play here. Education can help society as a whole and these people individually. It even helps lessen the violence in the prison while they are in there. If they are reading Shakespeare and writing papers for me, then they will definitely not have time for other things. They also need to remain without incident or else they cannot come back into the classroom, which is where they want to be. This helps everyone. CDCR is concerned with safety as it should be, and coming into the prison is a risk, but it is balanced by the improved attitudes, decrease in violence, and the increase in employment opportunities after they are released.

This semester I am teaching Shakespeare and Overview of Literature to a group of guys that I taught Composition and Reading to last semester. This is pretty unusual. The RSP likes to shift everyone around so that you do not teach the same students because you can get attached, but there are only so many professors and so I expect I will end up teaching students for multiple semesters. The reason this happened this time around is that last semester a student in another class walked by my classroom, asked me what I was teaching and then asked me what I could teach. I gave him a list, and he asked me if I could get Shakespeare in here. I said: get together an inquiry form with a list of students who want Shakespeare, and they will give it to you. They did, and many of my previous students signed up, and now I am teaching them Shakespeare. One of my students asked me about Sir Walter Raleigh when I was giving an historical context lesson. I did not know much about him other than he was a poet, so I returned the following week with a full-page of information about him. The student just knew that he was from the same era. I end up with lists of questions from them that I then have to research. Another student asked me last week if the people in the Othello movie we were watching are speaking the same language as the people in the Romeo and Juliet movie we saw a couple of weeks ago. I said: yes, it is all Shakespearean English. The ones we are watching now are just doing it with English accents. He said, how come I can understand this one and not the other one? I said: you are just getting it now. It is just easier. I did a little dance in the parking lot about it. It was a huge win! One of my students wanted more opportunities to publish his academic work, and now I am forming a committee to figure out how to get them more information about that. In a previous semester, a student showed me his proposal for a book club based on the informal discussions we got into in our Latino Literature class.

These students are hard working and thirsty for knowledge. I feel lucky to be able to teach them. I was recently at a conference about introducing board games into the learning environment put on by my colleague Dr. Christine Cruz Boone. Besides it being a wonderful idea, (The RSP are going to start trying to figure out how to do that in our work inside), one of the many issues that were discussed during this presentation is the lack of interest and general apathy of our on-campus students. The tap dancing we have to go through to get some of our students to participate at all is one of the many frustrations of our work as educators. Out of all the many frustrations about working in prison, this is not one of them. There is not much I would not do to teach students who are this engaged — no matter what they have done. They are working on themselves now, and they want to learn. It is important that we give them this opportunity to better their lives. Some want to put them away and forget about them, but they have inherent worth and dignity no matter what they have done, and we should treat them with justice, equity and compassion as human beings.